Rowan Castle - Travel & Photography

© Rowan Castle 2019

Brazil 2002 - Diary (Page 2)

down onto the rainforest, and in the near distance, dramatic mountains of the

Sierra Neblina. From this point onwards the landscape changed dramatically. We

left the trees behind, and trekked through a weird landscape of mud, palms,

bromeliads, roots, underground streams and quartz rock. As we neared Pico da

Neblina Base Camp, Val pointed out a large mound of loose quartz by the side of

the trail. It had been excavated by gold miners who intended to search it for

gold, but presumably hadn’t returned to finish the job.

The blue morpho butterfly wing that we found.

A rare view out of the rainforest, from near the pass.

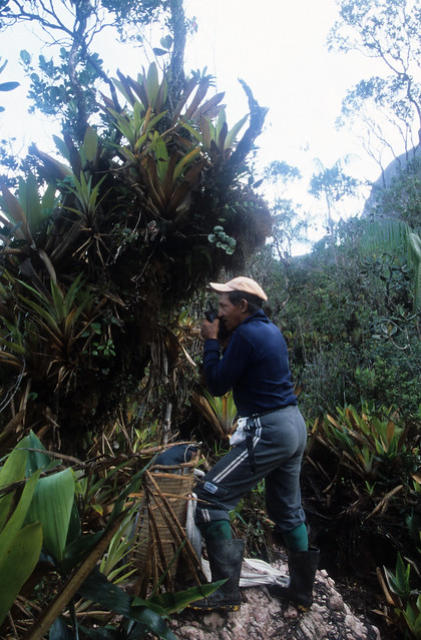

Me, approaching the base camp of Pico da Neblina.

I reached the Base Camp with Valdir, slightly ahead of the rest of the group.

There were a couple of existing frames for the shelters in place, and the porters

had already set up a blue tarpaulin over one of them to form the kitchen area.

The camp was located in a very pretty spot, at the junction of two small creeks.

It was obvious that gold miners had previously used the area, because there

were signs of old shelters and the ground had been stripped down to the quartz

gravel underneath. However, beyond the small clearing of the camp was an

incredible landscape of rocky outcrops, carpeted with palms, bromeliads and

other strange plants. It really was a ‘lost world’ and I half expected to see a

dinosaur at any moment! I set up my tripod and took a couple of photographs of

the camp, before James came down the trail. He told me that he and Bill had

discovered a beautiful orchid near the path and that I might want to come and

have a look. After a few minutes of searching, we found the right spot. Sure

enough, there was an orchid growing there with three small but stunning

flowers. It has been estimated by botanists that sixty percent of the plants on

the slopes of Neblina are unique to the area and new to science.

Our base camp on Pico da Neblina.

The orchid at base camp.

After I had set up my hammock in camp, I set off to explore the gully formed by

the larger of the two creeks. It seemed that this small river was actually the

beginnings of Tucano Creek that we had navigated earlier in the boat. A path led

a short distance along the left hand bank, but after that the going was far from

easy, and I found myself clambering over many large boulders. In the dense

undergrowth on the high banks above the creek, I occasionally saw

hummingbirds searching for flowers. Within a short distance from the camp, I

found a second orchid. It was not as spectacular as the one that Bill and James

had discovered, having only small yellow flowers.

After picking my way over and around the rocks, I discovered that the creek

widened into a beautiful and secluded area where the clear water flowed slowly

past a wide sandy shore. There were several flower-covered bushes on the

banks of the stream, and after a few minutes a dazzling green hummingbird

with white outside tail feathers flew in to feed on the nectar. It was a magical

spot, and I re-visited it several times before nightfall to show some of the rest

of the group.

Back in camp, Graham and I were chatting before dinner, when a green

hummingbird with an iridescent blue throat flew into our shelter. It buzzed

round our heads for a few seconds and then flew off. We learnt that the

hummingbirds in the area are fairly tame because they have seen few humans.

Also, the gold miners that live on the mountain have made a habit of feeding

them and so they associate people with food. Valdir had filled a plastic mug

with sugar-water and hung it up on a nearby branch. The local hummingbirds

took full advantage of this free source of energy and quite often perched on the

cup to feed.

Day 8 – Saturday 14th September (Summit Day).

The whole group was awake at 05:15 to ensure an early start for the summit

climb. We had a hurried breakfast, and in the pale dawn light Valdir gave us a

briefing on the climb ahead. He explained that there was a creek that had to be

crossed during the trek up the lower slopes, but it could not be forded after

heavy rain. This meant that if it started to rain heavily while we were high up

on the mountain, we would have to race back down to base camp to avoid being

stranded. He expected that reaching the summit and getting back to camp

would take at least twelve hours and it would be important for us to keep up

with his pace if we were to make it back before dark. Brian announced that he

would not be going with us to the summit, because he didn’t feel like it and

would rather spend the day exploring the base camp. Naturally, we were all sad

that he wouldn’t be climbing with us, but respected his decision. Before we set

off, Bill rummaged in his backpack and gave each of us one of the power bars

that he had brought with him from the US. It was very generous of him, and was

a welcome boost to our energies before what was sure to be a testing day. Each

of us took only the absolute basics with us on the trek to the summit – a water

bottle, waterproofs and our cameras. I also opted to take my GPS receiver with

me, because I wanted to get an accurate fix of the position of the summit.

A rare glimpse of Pico da Neblina - it is usually shrouded by mist.

We set out at 06:40, briefly retracing our steps back along the trail, before

following a left hand fork towards Neblina. This first took us through an area

that had been heavily excavated by gold miners and then plunged into a four

hour stretch of thick mud and tangled roots. There were high earth banks to

each side, and dense vegetation on top of these, so that we were trekking along

corridors through the foliage. Some of the mud pools here were more than knee

deep and it would have been so easy to break an ankle on the hidden roots and

rocks. Sometimes our legs sank deep into the black mud and it was so thick and

viscous that it was a struggle to break free. Another hazard were roots that had

been chopped through with a machete to clear the path. The cut ends of the

roots were often very pointed and if not seen in time they smashed painfully

into a knee or a thigh.

Reaching the creek that Valdir had warned us about, we found that fortunately

it contained very little water and was easily crossed. The banks of the stream

were crowded with vegetation, including a shrub-like plant with many beautiful

small pink flowers. After re-filling our water bottles we continued along the

muddy path.

At this point Valdir had gone far ahead, I was trekking a little way behind David,

and James was back at the tail of the group. I came round a bend in the track

to find that it forked. I was just in time to see David about to disappear out of

sight along the left hand fork, but I noticed that someone had bent two thin

saplings across each other at the mouth of that path. These indicated that the

left fork was not the way to the summit. It was a subtle sign that was easy to

miss, and David must have walked straight past it. I called out to him and he

rejoined me on the correct path. It was lucky that I saw him when I did. After

this incident I was rather concerned about how easy it was to lose the way and

decided that I would make an effort to catch up with Val at the front. It was

hard work to put on extra speed through the thick mud but I made it. Walking

behind Val seemed to make the climb easier, because he knew the terrain so

well. I reasoned that if I stepped where he stepped and kept to his pace, I

would have a good chance of making it to the top and back down safely. We

were also fortunate in that James and Val were equipped with two way radios

so that they could communicate fairly easily, even over some distance, and

keep the group together and on track. One consequence of moving to the front

of the group and trekking with Val was that I missed an interesting discovery by

James and Bill. They came across a small black scorpion resting in leaf litter at

the side of the trail. I have never seen a scorpion in the wild.

Valdir on the radio.

Having reached the end of the muddy section, we could see that the path

climbed extremely steeply up a cliff face. It was quite exposed in places, and

several short sections were actually basic rock climbs or scrambles. At one point

in the climb a trio of scarlet macaws flew past at eye level, giving us a welcome

distraction from the drop off nearby. I found one small rock chute particularly

difficult to climb, because the handholds were far apart and slippery because of

the water and algae on the surface of the stone. At another, there was a

permanently fixed knotted rope that allowed us to haul ourselves up. This

section of the climb was incredibly demanding, and there was no let up in

either the pace or the steepness of the ground.

After the cliff came an easier (but still steep) section over quartz rocks. The

plant life here was very interesting; we saw a beautiful orchid, carnivorous

pitcher plants and another interesting insect-eating plant, the bladderwort. The

bladderworts on Neblina grow in the small pools of water that collect inside

bromeliads. Once established they send up a single green stem, topped with a

beautiful lilac flower. The roots that grow inside the pool of water have little

sacks (bladders) on their ends. The plant pumps the water out of these bladders

to create a partial vacuum and when a tasty morsel floats close by, a trapdoor

opens in the bladder and the insect is sucked inside to be digested. We took a

rest at this point, while we examined the interesting plants. Unfortunately, I

had put my camera away and so missed the chance to photograph a beautiful

hummingbird that perched on the branch of a small tree, just feet away from

us!

Eventually, we reached the foot of some formidable looking cliffs and had our

lunch while perched on a steep bank of rocks. Looking at the way ahead, I was

beginning to wonder if I was going to make it to the summit. By this stage,

Carolyn’s knees were hurting badly, so she and Del decided to go back. Tomei,

one of our Yanomami porters helped her all the way back down to the base

camp. That left four clients, Bill, David, Graham and I, plus Marcello, Valdir and

James, to push on to the summit.

Just after the lunch stop we came to an almost sheer rock face some fifteen

feet high that was safeguarded by a knotted rope. I climbed up very carefully,

trying hard to keep a tight grip on the sodden and slippery rope. When I got to

the top I found a narrow ledge with a nasty drop off to the left, and I rested

against the rock while I got my breath back. Next to me on the ledge were the

troops from the Brazilian army unit who were on their way back down from the

summit, having completed their repairs to the flag. They were waiting patiently

for us to ascend before they could use the rope to get down. When the others in

our party reached the top, Valdir told me that the leader of the Brazilian army

unit wanted to talk to me and pointed him out. I made my way over somewhat

nervously; why on earth would he want to speak to me? The army man spoke

briefly to one of his sub-ordinates, who to my amazement began cutting the

Brazilian flag from his uniform. The leader then presented this to me, with a

salute. By now I was totally confused, and so I just saluted back and thanked

him. They made their way down the rope, and I turned to Valdir in the hope of

an explanation. Apparently, the leader of the army group had seen my very

short haircut (a number 3) and had assumed that I was in the UK army. He had

decided to give me the Brazilian flag from the uniform as a goodwill gift. I was

amazed, but very grateful and I still have the army patch that he gave me.

Me, climbing the final fixed rope before the summit.

The Brazilian Army unit. Thanks to Bill Scroggie for the use of this

photograph.

From this point the path to the summit was a very steep rock scramble that was

exposed in places. Fortunately, we were now amongst the clouds and they

shielded us from seeing just how nasty the drop offs probably were. Everyone

was very tired, and wondering how much further there was to go, when we

finally sighted the Brazilian flag fluttering above the summit cairn. A few

minutes later, and we stood on the roof of Brazil, at 9,888 feet (3014 metres)

above sea level. As I reached the top (at 12:04) I shook hands with Valdir and as

each member of the group joined us, we congratulated each other on

completing such an arduous climb. I marked the position of the summit on my

GPS receiver and then we took group photographs next to the flag. Each of us

signed the summit book, which Brasil Aventuras had placed underneath the

summit cairn in a tupperware box. I wrote:

“Rowan Lee Castle (British and Canadian) at 12:21 on 14th September 2002. A

stunning mountain!”

We spent about one hour on the summit, during which the dense cloud that

surrounded us parted briefly only once, to reveal a memorable view straight

down onto the canopy of the Venezuela rainforest on the other side.

Me, on the summit of Pico da Neblina, Brazil’s highest mountain.

Marcello and Valdir on the summit of Pico da Neblina.

Then began the long down-climb back to our camp. It was very difficult to make

our way down over the slippery rocks, and of course this time we were facing

the drop offs, which made it more unnerving. I had particular problems on one

steep section not far below the summit, and James took my camera and helped

me to find sturdy foot and hand holds. When we reached the knotted rope down

the rock face where we had met the soldiers, I went down first. It was more

frightening to descend than it had been on the way up, because I had to lower

myself backwards and the rope was very difficult to grip. I wasn’t surprised

when Graham asked James to belay him with the safety rope as he came down

after me.

We had a rest stop by the foot of the crags, in exactly the same place where we

had lunch. I took a photograph of James next to the precipice, with

neighbouring mountains as a backdrop. From this vantage point we could just

see the lip of the Rio Baria canyon, the deep and unexplored rift that cuts right

into the Neblina massif.

Our guide James at the rest stop. The lip of the Rio Baria canyon is on

the far right.

When we reached the treacherous cliff section, it was my turn to ask to be

belayed with the safety rope, to help me descend the awkward rock chute that

had caused me such difficulty on the way up. I remember another tricky part of

the cliff very vividly. It was another short scramble down a rock chute, onto a

very narrow path next to a big drop off. We had to climb down this facing the

rock, and the very last section was an awkward step backwards off one of the

footholds. As I stepped down, I overbalanced backwards and stumbled towards

the drop. Luckily for me, Valdir was watching my descent closely, and as I

stepped back, he put his arm out behind me and stopped me going any closer to

the cliff.

When at last we reached the foot of the cliff, it was time to retrace our steps

through the seemingly unending mud pools and roots that lay between the camp

and us. By this time we were all exhausted, my knees hurt with every jar from a

submerged rock or sharp contact with the end of a root. It really was difficult at

times to summon the energy to lift my feet out of the black mud ooze.

Exactly twelve hours after we had set out to the summit, we returned to our

base camp. Brian, Carolyn and Del all came out of their hammocks to

congratulate us and Brian passed around a very welcome hip flask full of Scotch

whiskey. I was shattered after the climb, which was definitely the most

demanding I had done. I had just about enough energy to re-arrange my pack

and eat my dinner of potato, rice and vegetable stew, before heading to my

hammock for some much needed sleep.

Sunset at Pico da Neblina base camp.

Day 9 – Sunday 15th September (Rest Day).

It had been an uncomfortable and chilly night in the hammock, with a cold

persistent wind blowing in under the tarpaulin. I had breakfast, with delicious

hot chocolate, and then I took my camera, zoom lens and tripod down the creek

to the magical spot I had found before. This was our rest day after the summit

climb, and I had decided to spend the morning relaxing by the creek and trying

to photograph the hummingbirds feeding on the flowering bushes. It was the

hope of being able to photograph hummingbirds in the wild that had led me to

bring along my tripod and zoom lens in the first place, and make the effort to

carry them all the way up through the jungle. I soon had my equipment set up

as close to the nearest flowering shrub that I could find, and then it was just a

matter of waiting patiently. I had read that hummingbirds are very territorial

and must feed constantly to stay alive, so I reasoned that I would have a fair

chance of capturing one on film. In the end, I discovered that a hummingbird

(perhaps the same one) visited this particular bush roughly every half an hour.

Even with the modern features of my camera such as fast auto-focus and a high

shutter speed it was very difficult to photograph these extremely quick and

agile birds. The action head on my tripod proved indispensable. It looked a bit

like the brake on a bicycle handlebar and with one squeeze of the lever the

head and camera could be swiveled to the desired position, but as soon as the

pressure was released it locked solidly in place. This allowed me to quickly

follow the bird as it darted around the flowers and fire the shutter as soon as

the head was locked in place. It took me the whole morning and an entire roll

of film to get a handful of shots that I thought might have worked. Fortunately

when I was back in the UK and had the slide film developed, I found that the

results from a few of the shots exceeded my expectations. I thoroughly enjoyed

that morning by the creek, and it was impossible to tire of watching these

dazzling little birds.

Yellow orchid flowers near base camp.

A hummingbird near the base camp on Pico da Neblina.

I got back to the camp just in time for lunch. As we sat around on the log

benches next to our camp a hummingbird flew up to us, and fed from the

plastic mug of sugar water, often when one of us was holding it! One bird flew

right into the middle of our group, hovered, and looked at each one of us in

turn before darting away.

A few of the others in our group had spent the morning up at the gold miner’s

camp. They told me that the miners had been very hospitable and even given

them some food. Unfortunately, the only thing that they had to offer was a

lump of animal fat that they heated over the fire. Bill told me that during the

cooking process, it quite often caught light and had to be hurriedly

extinguished. Bill had done his best to eat it, not wanting to appear ungrateful,

but said that it was almost inedible. Apparently the miner’s camp only consisted

of a pole shelter like ours, but with blue tarpaulins on all sides to try to keep

out the wind. They had rigged up many sugar feeders for the friendly

hummingbirds, which were constant visitors. The miners had been enduring

these extremely tough living conditions for eleven years. They had so little that

they used notebook paper to roll cigarettes. While I was at the base camp, the

three miners paid us a visit, and even showed us their precious stash of gold

dust.

A rainstorm blew in, the others retired to their hammocks, while I sat by the

fire in the kitchen part of our shelter, drinking cappuccino and chatting to Val.

While I sat there, a hummingbird flew in and tried to drink from my mug of hot

cappuccino! Then it moved on to trying to sip sugar from the lids of the bottles

of juice that we had. Val and I had to wave it away from the juice bottles,

because whoever bought the supplies had mistakenly got us diet ones for the

trek and these would be harmful to the hummingbird, because the artificial

sweetener would not give it the energy it needed to survive. These birds require

so much energy just to stay alive that they live constantly on the brink of

disaster, and I remember seeing a documentary that showed they could only

afford to stop feeding to go to sleep at night because they slow their

metabolism right down when they roost.

As the rain cleared I watched Val tidying up and doing tasks around the camp.

His jungle skills were remarkable. With a machete, he cut a nearby piece of

wood to the right size and within a few seconds had shaped one end to make a

new handle for our shovel. It fitted perfectly into the shovelhead at the first

attempt. When we had been trekking, I had seen him draw and throw his

survival knife in the blink of an eye, and he buried the blade right up to the hilt

in the stem of a banana tree.

My most remarkable encounter with the hummingbirds happened that

afternoon. I decided to sit out on one of the log benches and hold out the blue

mug full of sugar water, in the hope that one of the birds would feed from it. I

had quite a long wait, but eventually, one came down and actually perched on

my thumb as it drank from the mug! It was so light that there was hardly any

pressure from its little feet on my skin. I could feel the down draft of air from

its rapidly moving wings. It didn’t settle down completely, presumably in case it

felt threatened and decided to make a quick getaway. After a few memorable

seconds it finished drinking and flew off to the safety of a nearby branch.

We were all very glad that we had been given the chance to spend a day in this

incredible and remote place, and we also needed the recuperation time. My

legs and knee joints ached terribly from the descent the day before, and it was

the first time I had experienced anything like it, even after a long trek. Walking

any distance around the camp required a lot of effort.

After dinner, I was glad to retreat to my hammock once more, but it was not a

peaceful night. The temperature dropped considerably and a gusty wind

buffeted the shelter. I found it very difficult to sleep and couldn’t wait for the

sun to rise.

Day 10 – Monday 16th September.

I got out of my hammock at 05:30 and we had a breakfast of porridge before

setting off down the trail at 07:30. We went back down the same route that had

brought us up the mountain, so once again we navigated our way over and

around the roots, boulders and mud that made up this strange part of the world.

A steep and tortuous descent, that was hard on the knees, took us back down to

the forested ridge. The three gold miners passed us on the trail. We didn’t know

it at that point, but they were heading for Sao Gabriel and decided to come

along with us. This was to cause a great deal of friction within our group before

the trek was over.

Once again I was walking up front with Val, who was now setting a furious pace.

I could only just manage to keep up with him. Val and I arrived at Bebedo Camp

(where I had smashed my toe on a rock before) roughly half an hour before the

rest of the group, and this was where we all stopped for lunch.

The afternoon was a grueling trek along the undulating path, which took us to

our camp for the night at Bebedo Vehlo. This was the spot where Pepe had

caught the giant worm previously. Val and I were able to keep in touch with the

rest of the group by radio during the descent, although the ups and downs of

the terrain meant that often our messages were broken up or distorted. We

arrived at Bebedo Vehlo at about 16:30.

When everyone had made it into the camp we learnt that the gold miners would

be camping with us and were also going to be sharing our boat. As I mentioned

earlier, several members of our party were not at all happy about this. It didn’t

bother me particularly, as this is how life in the jungle works. If others need

transportation and are prepared to do their bit then there is not a lot that can

be done about it. Unfortunately in this case the miners tried to pacify the

opposition by claiming that one of them had suffered internal injuries while

digging for gold and needed to get to hospital. This patently wasn’t true, but as

I’ve said, I had no reason to object to them coming along for the journey back,

especially after they had been so hospitable to our party at the base camp. The

existing shelter at Bebedo Vehlo was old and rotten, and I noticed how all three

of the miners worked extremely hard to help our Yanomami porters to construct

a new one.

The new shelter was completed just in time. I had only just finished rigging up

my hammock and mosquito net when a terrific thunderstorm struck and the

jungle trees were rocked by a powerful wind. Suddenly I heard James shout a

frantic warning to us to get out of the shelter. I have never got out of a

hammock so fast! We all raced outside into the rain. James had rightly been

worried about the possibility of dead branches falling from the nearby trees and

landing on our shelter. Once the wind had lessened slightly we felt it was safe to

take refuge under the tarpaulin once again. The downpour was torrential and

we were forced to eat our evening meal standing between the hammocks.

Day 11 – Tuesday 17th September.

Today was our last day of trekking in the jungle. We trekked at a very fast pace

down to the Tucano Falls camp, where I had seen the big tarantula. Near the

clearing where we had camped was an old Yanomami plantation of banana

trees. We made our way between their stems until Val found a huge bunch of

bananas on the ground and handed them out. They were perfectly ripe and

delicious.

Val was concerned that the river we had forded before, that lay between the

banana plantation and the camp, may have risen after the rains and be too high

to cross. Luckily, this turned out not to be the case and the river looked no

different than during our previous crossing. It was very hot and humid here, so

we were all glad of the opportunity to have a refreshing swim before continuing

the trek. Val told us that when the Yanomami first came to this camp from

Venezuela, there had been a big battle between two family groups. He said that

the graves of seven Yanomami warriors lay up on the bank.

We paused briefly in our old camp, just long enough to sort out our rucksacks

and then set out again for the boat. I was up at the front of the group again

with Val, and when the trail took an odd turn or the route was difficult to see,

he cut saplings and put them across the wrong path so that the rest of the

group would not get lost. At one large fork in the path, the right hand branch

had a stick placed across it at waist height. Val said that this path led to the

Yanomami village of Maturaca after a few days of walking, but that the village

was out of bounds to foreigners by order of the government. However, if any

emergency had happened on Neblina to one of our group, they would have had

to be carried to the airstrip at Maturaca to be airlifted out. This was a sobering

reminder of how remote Neblina is and how difficult it would be to rescue an

injured trekker.

On the way to the boat Val and I saw several tiny leaf-coloured frogs that had

been encouraged to come out by the recent rain. We also disturbed a very large

brown lizard that shot off through the leaf litter as we approached. On one very

dark and dank stretch of the path we saw two brightly coloured heliconid

butterflies hovering over an orange flower. Amazingly they danced in the air in

the same spot long enough for me to get my camera out, let the condensation

disappear from the lens and get a photograph of them! It was very hot in the

jungle and probably the most humid day we had trekked on. The recent rains

seemed to have brought a multitude of insects to the tree canopy, and they

kept up a constant cacophony of noise. Nearing the boat we passed by several

menacing and turbid pools that lay in hollows in the forest floor. At one of

these, Val said he had often seen a large anaconda resting in the murky

shallows. We could clearly see a rut in the mud at the edge of the pool where

the great snake had slithered in and out of the water in the recent past. By this

point in the day my energy was starting to flag and I could not believe the pace

at which Val was walking. It was such a struggle for me to maintain the pace

that I felt faint on more than one occasion.

Heliconid butterflies in the rainforest.

At about 12:30 I finally reached the boat, and the jungle trek was over. I was

absolutely shattered and drenched by the humidity and my own sweat. I took

off all of my equipment, and sat fully clothed in the sandy shallows of Tucano

Creek – not caring that my pockets were slowly filling with fine gravel stirred up

by the current. The others soon arrived and joined me in the water for a swim.

After that we had a relaxing lunch on the riverbank and rested while the boat

was prepared for the return river journey.

It wasn’t long before the boat had been pushed back down Tucano Creek and we

rejoined the Cauaburi River. We saw many toucans, blue and yellow macaws and

oropendola birds (these have a yellow tail and a brown body). At one point we

even saw a snake swimming across the river. It was a non-venomous whip snake

and was black with white bands.

We stopped for the night at Maria Camp. I think there comes a point on any trek

where I suddenly feel very at home in my surroundings, and that happened this

evening. Darkness had fallen, and I had gone down to the long sandy shore near

the huts to wash in the Cauaburi River. As I stood knee deep in the tea-brown

water, shaving by the light of my head torch, the stars were twinkling in the sky

above the dark outline of Padre Peak. The night was perfectly still with no

breeze and even the flowing river made little noise. The jungle was quiet and

eerily beautiful and I knew that I would be sad to leave it behind.

At dinnertime, a German couple and their guide who were on their way up river

to Pico da Neblina joined us. They were planning to take a tent with them and

camp overnight on the summit under the full moon.

We set up our hammocks in one of the Yanomami huts, as we had on our

previous visit. As we were tying them in place, we noticed that an enormous rat

was staring at us from the roof. It had brown fur and a white underbelly. It

didn’t seem to mind that we were there at all, and we let it be. As we climbed

into our hammocks for the night we got a nasty shock. The timbers of the hut

were quite rotten and began to give way. At first we thought we might have to

move huts or sleep on the beach, but fortunately we managed to get round the

problem by tying our hammocks in a slightly different way.

It was difficult to get to sleep at first because the gold miners had their radio

on at a high volume in the next hut. They were listening to a match involving

their football team – Sao Paulo.

Day 12 – Wednesday 18th September.

I had slept well during the night, but been badly bitten by mosquitoes. Today

was the final leg of our river journey back to the road at Llamarim Creek. I had

my Global Positioning System receiver switched on for most of the way, so I was

able to trace our progress back past the waypoints I had logged on our outward

journey.

Our boat moored at Maria camp, with Padre Peak behind.

The only thing of special note that we saw during the morning was a very big

dead snake that was lying on a fallen tree branch in the river. Decomposition

had begun to fade the colours and patterns on its skin, but Val said he thought

it was an anaconda.

We stopped for lunch on Jaguar Beech. I had a swim in the river, and once again

we were lucky enough to see a pink river dolphin.

In the afternoon our journey became more difficult. Our outboard motor kept

surging and then cutting out, leaving us drifting in the middle of the river or

entangled in the undergrowth on one of the banks. The engine belonged to one

of our Yanomami porters, Tomar, who had bought it for R$ 6000 with his

severance pay from the Brazilian army. He now earned an income from renting

it out. Our boatman then had to remove the sparkplug and clean it before we

could continue. When we reached the FUNAI post, Valdir went ashore briefly to

talk to the owner of the house and tell him that we were all safe and out of the

National Park.

Shortly after we set off again from the guard post, our engine problems came

back with a vengeance. It appeared that our boatman did not have a spare

sparkplug, and I looked on nervously as he began bending it into shape with a

screwdriver. Somehow he managed to coax the engine back to life and we went

on our way. It was reassuring that Marcello had brought a satellite phone with

him, and presumably could have summoned help if we had been stranded.

In the middle of the afternoon there was a terrific thunderstorm and torrential

rain. I got soaked to the skin before I was able to put on my waterproof jacket,

and by that point the rain was so fierce that we all took cover under a blue

tarpaulin that had been placed over our heads and across the boat. One

lightning strike hit the forest very close to us, there was a tremendous bang and

we saw a bright yellow flash.

Eventually the storm died away, but by now I was wet and cold. The sun was

going down too, and the air temperature dipped considerably. We were still a

long way from the shelter at Llamarim Creek.

Darkness fell as we began to motor up the La Grandi River. By the time we

reached the entrance to Llamarim Creek there was no light at all. Pepe had to

stand up on the stern and shine a powerful torch so that our boatman could

steer a path through the trees and submerged branches. I switched on my GPS

receiver and turned on the backlight so that I could see exactly how far we had

to go to reach our camp at the road. With about one kilometre still to go, we

got stuck in a couple of places where the boat ran up on submerged branches.

Val and Pepe had to get out of the boat and into the inky water to push us back

off – dangerous work in the dark.

My GPS showed that there was just a hundred metres to go before we reached

our camp, but I could see nothing. There was no sound except for our engine

and no lights but our own torches. In fact, we saw nothing at all until we

reached a huddle of boats that were tied up at the creek. When I climbed out

of the boat and onto the bank, I was cold, wet and stiff from sitting on my

bench seat for many hours. I was looking forward to changing into my dry

sleeping clothes and climbing into my hammock.

Our accommodation for the night was the wooden shelter that we had seen at

the start of our journey. Sharing it with us were many Yanomami Indians who

had come from Maturaca (and possibly other villages) to trade at the roadside.

In particular, they had brought many bundles of jungle vines with them to sell.

These were identical to the bundles I had seen at the Yanomami traveling camp

in the jungle, and as I mentioned earlier, these are made into yard brushes. I

set up my hammock on the upper level, and changed into my dry clothes. While

I was waiting for dinner, Val came over and suggested that everyone should keep

a close eye on their possessions, as there were so many strangers around.

However, there were no problems with theft at all.

Our porters set to work cooking our dinner, and after we had eaten we all

retired to our hammocks for the night.

Day 13 – Thursday 19th September.

I had slept well, and woke up at first light. Our incredible journey into the

Brazilian rainforest was now at an end, and we packed away our equipment and

waited for the off-road taxis to arrive. We knew that it would probably take

them at least three hours to make their way from Sao Gabriel. When they

eventually arrived, we were all amazed to find that they had remembered to

bring a crate of Coca-Cola with them, that Marcello had ordered for us. Not

only that, but they had been transported in a cool box! We were all in very high

spirits now that we had successfully completed the trek and were about to head

back into town.

Once again, the drive down the road through the forest was very enjoyable. It

seemed much hotter than before. There was not a cloud in the sky and the

tropical sun was extremely fierce. The heat didn’t bother the butterflies

though, and great clouds of them flitted and danced above the road and along

the verges. As before, we had to stop regularly and get out so that our truck

could make its way across the rutted sections, and once or twice our vehicle

even had to tow the smaller Ford 4WD across the worst parts. On the way,

Valdir decided to give me the brightly coloured necklace made of plastic beads

that he had bought from a Yanomami Indian.

Our first stop in town was at a petrol station. While the truck was re-fuelling we

all got out, bought some beers and drank them in the sunshine. I think it’s true

to say that no matter how fascinating and beautiful the rainforest is, nothing

lifts the spirits more than finally getting out of it!